Notes on Porting a UNIX Classic with Cosmopolitan

(updated April 28, 2025 to reflect new info from comments on the Hacker News post)

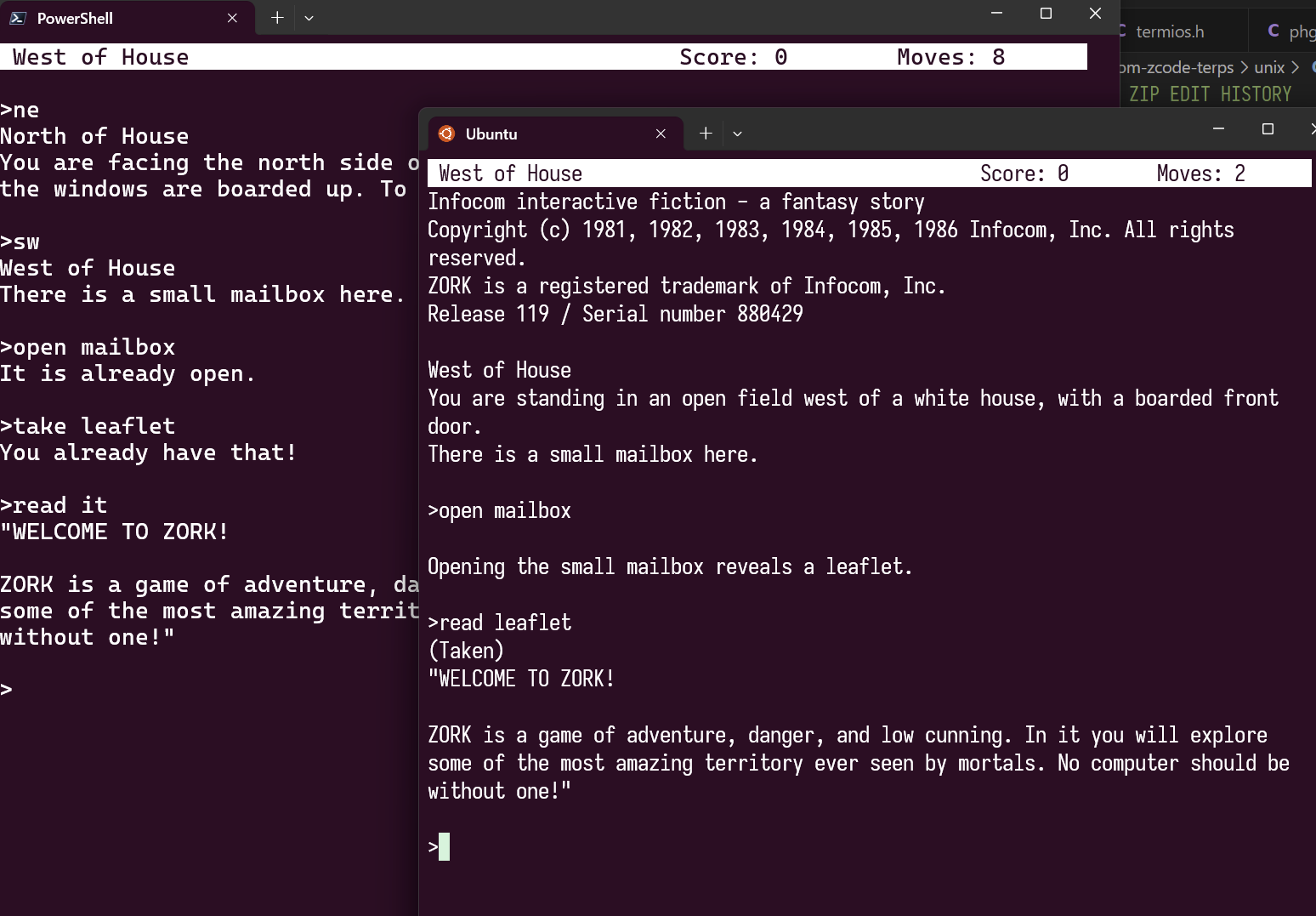

I made standalone executables of the Zork trilogy, ported from original Infocom UNIX source to Cosmopolitan, are available for Windows/Mac/Linux/bsd for arm/x86 machines. These require no further installation nor external files to play.

Here’s how to download and play Zork on the CLI:

wget https://github.com/ChristopherDrum/pez/releases/download/v1.0.0/zork1

chmod +x zork1

./zork1

# This one executable runs on any and all targetted platforms

# `zork2` and `zork3` are available, for trilogy completionists

# Windows users, add `.exe` to the downloaded file to make Windows happy

# Linux users with .NET Mono libraries might need to run `sh ./zork1`

Want to run an arbitrary .z3 text adventure file?

Download the z-machine from here

About the project

Recently I published v3.0 of Status Line, a project which makes Zork playble on the Pico-8, onto three major operating systems. With that deployed successfully (is there a ‘knock on wood’ emoji?) I turned to porting Infocom’s original UNIX z-machine source code through the use of Cosmopolitan. After about six hours on a lazy Sunday I had it ported to six major operating systems, including Windows.

Unlike Status Line which relies on the Pico-8 virtual machine host, this port runs natively on all supported systems. Even better, thanks to Cosmopolitan magic, there is only one distributable to maintain which can conform itself to run on whichever operating system is running it.

Here’s the story of how and why I decided to do this project and what I learned along the way.

What is a Z-Machine?

Over the years I’ve spent a lot of time looking at and thinking about the Infocom z-machine. Briefly put, Infocom text adventures were released as platform-independent game files which ran within platform-specific virtual machines for every system the company supported. The spec for that virtual machine is known as the “z-machine.”

I don’t know if they were “the first” to ship a commercial product using a VM on home computers, but they were definitely one of the first. In the 1980’s, unique computer platforms were released at a dizzying rate (Zork 1 released on at least 18 platforms) so it was important to be able to pivot onto new systems quickly. By using a VM, Infocom could rapidly bring their entire library of games to any new machine.

UPDATE: Commentor ssrc noted in the Hacker News post that quite a few vms shipped for home computers before Zork, especially in the development community, as with Forth, Apple Pascal, and others. Scott Adams’s adventures also used a kind of vm, and he beat Zork to market.

These days gamers have a plethora of choice for modern z-machine interpreters, but back then it was proprietary code. Only Infocom could make a z-machine interpreter which they dubbed ZIP, “Zork Interpreter Program.”

ZIPs were mostly written in hand-tooled assembly, unique to each platform, to squeeze maximum performance out of minimal (16K?! 1.774Mhz?!) hardware. But they weren’t all written in assembly; there also existed a UNIX ZIP, written in C. I don’t know assembly very well at all, but I absolutely know enough C to be a reckless tinkerer. I lazily wondered if that C code would build for me, unchanged, as-is. One compile later I had my answer: no.

I’m nothing if not tenacious, and the z-machine is an area in which I have better-than-average knowledge. Bringing this back to life felt like a perfect project to help me continue exploring the historical side of Infocom while also being simple enough to let me explore the potential of Cosmopolitan.

What is Cosmopolitan?

Put simply, Cosmpolitan is Justine Tunney’s brainchild to transform plain ole’ C into a “write once, run anywhere” language. Consider the typical approach to achieving such a goal, for example Java, WASM, and even the Infocom z-machine itself.

In the typical case, code is written in a unique (even domain-specific) language and compiled into custom byte-code. In the Java/z-machine cases, the promise of “run anywhere” is facilitated by a bespoke virtual machine, custom built for each target platform, which consumes the custom byte-code and runs the program. For WASM, that virtual machine is typically the web browser, though standalone options exist.

In Infocom’s case, a compact interpreter was bundled on disk with each game. Running it was a transparent experience, because launching the interpreter would auto-launch the bundled game file. From the user perspective, she was just launching a game. In reality she was launching a VM which launched the game.

That which unites us

Cosmopolitan takes a different approach to “write once, run anywhere.” Rather than creating a virtual machine tuned to each machine’s unique differences, instead it flips the script and evaluates the similarities of modern machines; what has stayed consistent over time? A common ABI, using standard C library calls, is designed around those shared roots.

Justine also noticed that executables on each platform have more in common than not. The APE format she developed, Actually Portable Executable, is structured very much like a .zip archive (not the Infocom ZIP!) and contains native code for all targeted platforms. After a build and compile, the resulting application will “run anywhere” because it is native everywhere; no virtual machine needed.

Bananas for APE

An APE file built against the Cosmopolitan project’s libraries can be given to almost anyone on a 64-bit machine, of any OS, by any maker and it will run. We do not need to do separate builds for macOS x64, macOS M-series, Windows 8, 9, 10, 11, Ubuntu, pick-a-Linux, BSD, etc. A single build can run on almost any modern machine.

For this project, this meant that whatever weekend effort I put into getting Infocom’s ZIP to work again could potentially serve a disproportionately large audience. As well, I wouldn’t need to worry about tweaking things per-platform, or crafting complex makefile incantations. I could focus on game correctness and ignore the platform-specific vagaries. I found this approach to be mentally freeing.

An additional benefit of the APE’s .zip archive roots is that we can take things further and create self-contained executables which embed the z-machine and a game data file into one standalone package. This makes for a very interesting distribution option, IMHO.

Coding Like It’s 1985

My day job is in Swift and Objective-C, and my weekend projects tend to be in Lua for the Pico-8. I dip into C from time to time, but my experience is firmly within modern coding conventions. I had never been introduced to K&R-style C, but this code from 1985 quickly forced the acquaintance.

As a first-timer to the K&R style, the main thing I noticed is how much is “assumed.” For example, for functions which don’t declare a return type, int is assumed. even if the function actually returns nothing. Some do return ints. Some return char but do not declare a return value, so the calling function assumes int in a kind of implicit casting.

Function parameters are only enforced by “trust” in forward declarations; they don’t need to be declared. And heck, why even bother with a shared forward declaration at all when you can locally forward declare external functions within a calling function?

if statements using THEN instead of braces? I guess you had to be there.

UPDATE: Commentor ganache on the Hacker News post notes that this is not a K&R style if/then. Rather, THEN has been defined in the original source header as a no-op. Commentor pcwalton says it comes from Bergenol.

This is all to say that it took time to adjust my reading comprehension skills for the code and make sense of what I was looking at.

The Repairs

The repairs necessary to get this source code to compile and work were, honestly, quite simple. The changes boiled down to three areas:

- Handling NULL

- Function declarations

- Deprecations

NULL and NULL and NULL

NULL in the original codebase was defined as:

#define NULL 0

Then again later, in the same file:

#define NULL 0 --not a typo; it was double-defined.

Of course in modern C libraries we define NULL as:

#define NULL (void *)0

This gave us three definitions of NULL for the project. Fun! But we only need one. Untouched, this caused compilation to fail with code such as this (that K&R if/THEN works fine!):

newlin()

{

*chrptr = NULL; /* indicate end of line */

if (scripting) THEN

*p_chrptr = NULL;

dumpbuf();

}

The assumption and kind of “contract” for NULL in the year the source was written was, as we saw, #define NULL 0. If that’s what they wanted, then that’s what we’ll give them.

newlin()

{

*chrptr = 0; /* indicate end of line */

if (scripting) THEN

*p_chrptr = 0;

dumpbuf();

}

Function declarations (and the lack thereof)

A lot of compilation errors were related to functions being called that hadn’t been declared yet. This was fairly trivial to handle; here’s an example of the pattern used in the original code.

UPDATE: Commentor o11c on the Hacker News post noted that these flags are useful for this problem.

-Werror=missing-declarations -Werror=redundant-decls

char *getpag(ptr, page)

char *ptr, *page;

{

short blk, byt, oldblk;

char *makeptr();

pagfault = 1; /* set flag */

byt = (ptr - dataspace) & BYTEBITS; /* isolate byte offset in block */

if (curblk) THEN { /* in print immediate, so use */

blk = curblk + 1; /* curblk to find page */

curblk++; /* and increment it */

}

else

blk = nxtblk(ptr, page); /* get block offset from last */

ptr = makeptr(blk, byt); /* get page and pointer for this pair */

return(ptr);

}

OK, first we have to wrap our heads around how type declarations for passed values are declared after the function header. Again, we’ll let our eyes glaze past the use of THEN. Rather, please notice char *makeptr(). That is a locally scoped forward declaration for a function that is defined later; its real header looked like this:

char *makeptr(blk, byt)

short blk, byt;

{...}

Notice how the previous forward declaration didn’t bother with pesky function parameters. What does makeptr() take? Wishes and dreams, from the looks of it!

I switched all functions headers to use modern conventions, turning the makeptr definition into a format I’m sure most reading this have at least a passing familiarity with.

char *makeptr(short blk, short byt)

{...}

I collected all function headers into a big block of forward declarations at the top of the .c file and swiftly (well, tediously) eliminated perhaps 80% of compiler warnings and errors. With a clean set of forward declarations, all locally scoped declarations threw errors, making them easy to target for elimination.

Deprecations

The times they are (were) a changing. There were a few things that simply shifted how they needed to be done.

srand()seeding was quite complicated. I don’t know if this was just “how things worked” back then or what, but here’s what was in place.mtime() { /* mtime get the machine time for setting the random seed. */ long time(), tloc; rseed = time(tloc); /* get system time */ srand(rseed); /* get a random seed based on time */ return; }which I replaced simply with the below. “Good enough for government work” as the saying goes.

mtime() { srand(time(0)); }- The

backspacekey on my particular keyboard sends ASCII 128, but the original source code only ever expects ASCII 8. Simple enough to add another value check to allow backspacing on game input (to erase your typed command). sys/termio.hhas been supplanted bytermios.hand its attribute set/get calls were updated accordingly.struct termio ttyinfo; ttyfd = fileno(stdin); /* get a file descriptor */ if (ioctl(ttyfd, TCGETA, &ttyinfo) == -1) THEN printf("\nIOCTL - TCGETA failed");becomes

struct termios ttyinfo; ttyfd = fileno(stdin); /* get a file descriptor */ if (tcgetattr(ttyfd, &ttyinfo) == -1) { printf("\ntcgetattr failed"); }

cosmocc -o zm phg_zip.c -mtiny

Thanks to cosmocc, Cosmpolitan’s compilation tool, that single line got the z-machine up and running on 6 modern operating systems. No makefile, no per-system compilation shenanigans, no conditional code on my part. Almost embarrassingly simple, Cosmopolitan allowed me to target a hardware-agnostic ABI, and apply only minimal (often superficial) patches to the original source code.

Let me just say that seeing Zork’s famous introduction spring to life from within the sleeping source code of the very company that created it was a really special moment. After spending so much time on Status Line over the years, I expected to be jaded by “West of House” yet again. To be honest, it was quite the opposite. Knowing the history of the codebase and its place in the legacy of computer gaming only enhanced that feeling of discovery and exploration.

But We Can Go Further

APE files have a secret hidden superpower. The Infocom z-machine takes a -g flag at the command line, followed by the path to a .z3 data file to launch a given game. It is actually possible to embed that launch flag, and its related data file, into the APE file itself. The game will then, on launch, check itself internally for pre-populated launch arguments, which can reference internal data structures for specific data files.

Think of a macOS app, and how it is actually just a folder of executables and data which can be trivially viewed as such. We can use the APE format similarly. To make this work, we need two pieces:

Embed the .args and data

Create a file called .args which reads -g/zip/game_filename.z3. This is similar to how we would launch a game from the command line, but with a zip/ path prefix. That is the internal, relative position where these data files live. To make further manipulation of the executable easier, rename zm to zm.zip. Copy your .args file and related .z3 game file into the zm.zip file with

zip -j zm.zip .args /path/to/game_filename.z3

Tell the app to look for embedded .args

The executable proper needs to be told to look for embedded .args. Cosmopolitan has a handy command which does precisely that, which we call at the very start of main()

#include

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

int _argc = cosmo_args("/zip/.args", &argv);

if (_argc != -1) argc = _argc;

...

That will populate argv with the embedded args as though they had been manually passed by the user at the command line. The repo includes a makefile with an embed command which will do all of this busywork for you. Rename the zm.zip to whatever you want to call this standalone build. If you’re on Windows, don’t forget the .exe file extension.

Some Unsolicited Advice

As a first project to understand both the process of porting older UNIX code to modern C as well as how to use Cosmopolitan, it proved invaluable to work on something within my wheelhouse. I knew intimately what a z-machine should do, and how it should look and feel. I understood ahead of time the scope and goal of the project, and I also knew when something wasn’t working right (looking at you fflush(stdout)). Subject familiarity is invaluable in providing intuition when something is wrong, and can even provide foreknowledge for how to tackle certain classes of repairs.

When you compile and see a huge list of warnings and errors, don’t panic. Don’t fret. Don’t feel defeated. Rather, think of it as your “to do” checklist, then buckle down, and attack those compiler errors one by one. In the compiler, you can use the -w flag to turn off warnings and solely focus on errors. We don’t really want to do that for shipping products, but if you’re only interested in getting something kick-started and working for fun, it can definitely pare a “to do” list down into something manageable as you acclimate to the source code.

Lastly, I really cannot stress enough the ease of development that Cosmopolitan provided. The cosmocc compiler, itself built upon gcc, is an APE and as-such is a self-contained compilation ecosystem, bundled with the Cosmopolitan Libc drop-in replacement to the C standard library.

I’ve spent so much time in the past getting $PATHs set up, putting libraries in the right place, installing dependencies, trying to get MSYS2 to behave, and more that to have the convenience of a single APE application unified across my machines was a feeling of, “Yes, this is how things should be. It should be this simple.”

I hope you have the same positive experience.

Playing Z-Machine Games

A pre-compiled APE build of the z-machine is available for 64-bit systems on my github along with notes about how to use it. Standalone builds of the Zork trilogy are also available there, to demonstrate the power of the APE format. Remember, this project essentially reflects the state the code was in in 1985; I make no guarantees of its robustness nor accuracy! But that’s not really the reason to check it out, I think. If you seriously want to play interactive fiction, there are numerous better options than this port.

No, the reason to play this for yourself is to appreciate a singular, historical moment; to experience that brief feeling of reaching back in time and making a connection to a significant object from the past.

That’s not without merit, I think.